13

The

Rule of Law

Rh’aiiy’hn

of Old Rthfrdia woke slowly, blinking in the sunlight that was streaming

through his narrow, barred window, and knew he was himself again. Very weak,

but all there. Last night’s sleep seemed to have cleared the mists from his

brain.

He lay

quietly in the sun for some time, letting thoughts form and dissolve. It was

very early in the morning: the days were getting longer. He must have been here

for... many weeks, at all events. His brother was not here: good. Rh’aiiy’hn

sighed. If only things had been different, they might have— Oh, well. There

were several minds present, however: some awake but most asleep. Drouwh’s dog

must have gone with him, thank the bears. A little, bright, enquiring mind was

watching his. A cat? Prince Rh’aiiy’hn smiled slowly. A little cat was watching

and listening. He examined its mind carefully but it bore him no malice:

indeed, was incapable of such, he found. He sighed a little. Lucky little cat...

Yes, The Old Woman was there somewhere, too,

if only very faintly, but Rh’aiiy’hn knew without having to think about it

that, though she was certainly capable of malice, she bore him none. She would

watch and wait and probably never act directly to interfere in the lives of the

people: that had never been The Old Woman’s way. The Regent of Old Rthfrdia,

who wore the colours of all clans and owed allegiance to none, wondered once

again where The Old Women had come from and if their existence had a purpose—and

whether, supposing it did, this purpose might have a meaning that his people

could understand. Had he had to choose an answer to this last question he would

have said that on the whole he didn’t think so: if purpose could exist in a

Known Universe that to his wide-ranging mind was as unknowable as it was to the

tiny minds of the smah-birds, then he inclined to the theory that that of The

Old Women was connected to something bigger and of a far different scope than

the destinies of a few million humanoids on a small planet near the rim of the

two galaxies. But he would rather not have had to choose an answer: his feeling

was far more nebulous than this. Rh’aiiy’hn smiled a little and listened to the

smah-birds in the forest, and sensed the nyr, further in the leafy depths, and

felt at peace. Later he should make decisions, take charge of his life, but

just for now...

He must have

slept again: the sun was higher in the sky, there was activity in the house,

and the minds of its occupants jostled and chattered. He glanced at them and

dismissed them. The one mind that he was looking for wasn’t there. Then he

thought to check the little cat again. There was an instant’s shining awareness

and then a far more powerful signal overrode the little cat’s. Rh’aiiy’hn of

course did not translate the message into words, he had had no need to do that

for over thirty years, now: but what the mind was sending was a very simple

message that could have been summed up as a partly-annoyed, partly-amused Very clever!

I thought it would be aware of you, if any

of them were, he responded. He was aware of a wincing reaction, and

apologised for his loudness. He received an instant’s slightly scornful

amusement. Then he realised the mind had closed itself off from him. For a moment

he was shaken by a black anger.

I can still hear you, it sent.

Bears’ claws! cried Rh’aiiy’hn. What

good is that to me?

For a moment

he thought it had withdrawn entirely and regretted his rashness; then a cool

reply came, pointing out that that was scarcely the point.

What do you want? asked Rh’aiiy’hn

bitterly. What are you here for?

There was a

long moment of nothingness, and Rh’aiiy’hn of Old Rthfrdia, who had thought

he’d known what loneliness was after those interminable years as Regent, when

to make a friend was to risk making a thousand enemies, to trust another being

was to risk his own and the boy’s necks and the throne of Old Rthfrdia itself,

knew that until this instant he had known nothing of what it was to be truly

alone.

Then the

mind sent with a sort of cool amusement: Command

is always lonely.

He was

filled with such a shattering relief that he could barely respond at all. Yes, he managed at last. Who are you? How do you know that?

He felt

hesitation but was very sure that he was being allowed to feel it. Then the

mind sent simply: The food’s all right

now. Eat a lot, you'll need your strength. Drouwh Mk-L’ster’s away. I’m not

going away, but you won’t be able to reach me. Don’t try, there are minds here

who can pick you up.—Rh’aiiy’hn bit his lip.—There came an afterthought: Don’t contact the little cat, the boy reads

it.

Then he was

achingly alone again.

“He’s

stopped,” reported T’m over breakfast, his head tilted to one side.

“Where’s

A’ailh’sa?” asked Jhl hurriedly.

K’t-Ln’s leg

was improving and one of the clansmen brought her downstairs every morning,

now. She ceased spooning up yi’ish to report, with a face: “Her Ladyship has

the migraine and is confined to her pit. –Menstruating,” she translated kindly.

Jhl had much

ado not to laugh. “I see.”

“She’s just

feeling a bit sorry for herself,” said M’ri on a weak note. “I’ll take her up

some khyai’llh tea in a bit.”

“He’s not

dead, is he?” pursued T’m relentlessly.

“No, I can

feel him: he’s sort of resting,” pronounced K’t-Ln.

“Oh.” He

concentrated. “Yeah, you’re right. Hey, Roz, do you know who he is?” he asked

on a cautious note, one eye on K’t-Ln.

She

shrugged, and examined her nails. “It’s none of my business. –Oh, dear, my

nails really need re-culturing, this rough country life’s doing them no good at

all.”

K’t-Ln drew

a deep breath. “Just listen for a minute. –You, too, M’ri: leave that

plasmo-blasted washing-up!” she shouted.

M’ri came

over to the table, wiping her hands on her apron, looking nervous. “What?”

“He’s the

Regent, that’s who he is, in case anybody here really didn’t know it,” said

K’t-Ln with a hard look at the Pleasure Girl, “and whatever the political ins

and outs of it might be, The Mk-L’ster’s holding him here against his

will!"

“So?” said

Jhl blandly.

“Look, don’t

act dumb with me!” she said heatedly. “You’re the one that told me and T’m to

ask the Encyclopaedia about acts and planetary law and being-rights and stuff!”

“That

doesn’t mean I want to get mixed up in some pre-Fed dispute on a primmo dump

like this, though.”

This seemed

to go down fairly well: K’t-Ln glared, but not as if she wasn't convinced, and

continued: “Well, according to the Encyclopaedia, no-one’s allowed to upset the

status quo on a pre-Fed world.” She looked suspiciously at Roz, but the

Pleasure Girl only drawled: “So?"

“So The

Mk-L’ster’s gone and done it, he’s broken Feddo law!” cried K’t-Ln loudly.

“He’s been all right to us, though, K’t-Ln. I

mean, he got The Old Woman to fix your head and everything,” said M’ri.

“That it was

his fault that I hurt in the first place? Yeah. Anyway, I’m not talking about

that. Look: what I was thinking was, suppose we let the Regent go, do you think

he’d promise not to, um, tell on The Mk-L’ster?”

Her siblings

were goggling at her in a sort of blank horror, so Jhl said, somewhat feebly:

“You mean make him swear not to prosecute him, before you let him go?”

“Yeah!” she said eagerly.

“Doesn’t it

depend on what his priorities are?” asked Jhl limply.

“Um, how do

you mean? –Oh,” she said, reddening.

“Yeah, he

could swear he’d do anything!” put in T’m eagerly.

“Don’t be

stupid!” cried K’t-Ln. “He’s a man of honour! Roz didn’t mean that! –Did you?”

Jhl

reflected she could always erase the whole lot, if she needed to. “Not quite.

He is a man of honour, T’m, but there are some situations where there’s a

greater good and a being would feel it would have to break its word.”

T’m scowled,

but didn’t say that was what he’d said.

“For the

good of the people!” said M’ri eagerly.

“Yeah,”

conceded K’t-Ln grudgingly. “Pretty much.”

“Well, for

what he conceives to be the good of the people,” said Jhl weakly. “The trouble

seems to be that he and Mk-L’ster don’t agree on that.”

“Choice

542,” said K’t-Ln on an uncertain note.

“Doesn’t the

Regent want all the clan lands to go to the clanspeople?” recalled M’ri

foggily.

“YES!

Ghrr-brain!” shouted K’t-Ln angrily.

“Yeah, so we

gotta let him go!” said T’m eagerly.

“NO!”

shouted K’t-Ln furiously.

“But you

just said—”

“I don’t

wanna let him go because I agree or disagree with him, or with The Mk-L’ster—in

fact I think we’d be better off if all the Lords and the Royal Family were thrown to the bears and forgotten about!

And if you imagine for one minute the clan lands’d be safe in the hands of

idiots like that lot from the village you’re the biggest ghrr-brain in the two

galaxies!” cried K’t-Ln angrily. “All I’m saying is, it’s illegal for him to be held prisoner and the situation changed now,

while we’re in Pre-Fed, see? And we oughta do something about it,” she ended on

a sulky note.

“I don’t

exactly see...” quavered M’ri.

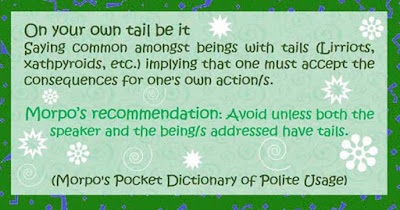

Very red, K’t-Ln said angrily: “The Rule of

Law! –That’s right, isn’t it, Roz? It’s what makes the Federation different

from all the worlds beyond the Outer Rim. And—and if we know about this and

don’t do something about it, then—then we don’t deserve to join!”

Jhl

perceived that the grey-green eyes were full of excited, angry tears. Oh, dear:

there was nothing like a young being filled with the fervour of its first grasp

of the great abstractions for intransigence. “I wouldn’t go that far, K’t-Ln,” she

said temperately. “You’re just a few beings: your whole planet won’t be judged

on the basis of your behaviour.”

“But what The

Lord’s doing is WRONG!” cried K’t-Ln.

“Yes, I

think so,” agreed M'ri.

Jhl rubbed

her chin. “We could use my lifter to get Rh’aiiy’hn away,” she said slowly.

“Yeah!”

agreed K’t-Ln, brightening.

“Where to?”

asked M’ri.

Of course

Jhl had been through all this in her own mind a megazillion times;

nevertheless, possibly four heads were better than one. “Anywhere. Dump him in

the Southern Continent until after the Referendum?"

After a

moment T’m said: “That wouldn’t be putting things back the way they were,

though.”

“Er—no,” she

admitted. “Very true.”

Sourly

K’t-Ln admitted: “One way the odds are stacked in The Mk-L’ster’s favour, and

the other way, they’re stacked in the Regent’s.”

“Exactly,”

said Jhl with a sigh.

There was a

short silence.

“Oh, dear,”

said M’ri faintly.

T’m began

excitedly: “We could still— No, we can’t,” he said. “Kna shit.”

“It’s the

classic definition of a dilemma, in fact,” noted Jhl drily.

T’m bounced

up. “I know! I’ll ask the Encycl—”

He’d taken

one and a half strides before Jhl immobilised him as she once had the little

striped cat.

“Let him

go!” shouted K’t-Ln, turning puce. “I know it’s you, don’t pretend!”

Jhl had been

aware for some time that the Regent had heard the entire exchange. Now he sent

very clearly: I am receiving very

confused images of your physical being but I know that, whoever you are

pretending to be, you don’t need to hurt these children in order to protect

yourself. Of all the personalities in this house, it is they whom you can

trust. –You and I.

Much of what

he thought he was seeing of her was through the eyes of the tiny cat, so it was

hardly surprising the images were confused. T’m’s Kitten didn’t see Pleasure

Girl Roz at all: it conceived of Jhl as a collection of feelings and odours

that it interpreted in its own way, which was very far from that of a humanoid.

She smiled, just a little, and said to the two scared girls: “I think you might

have heard him sending just then: that message had no specific target.”

“He can’t

feel you at all,” said K’t-Ln in a wondering voice.

Jhl gave her

a mocking look. “Can you?”

“I can— I

suppose I can feel what you want me to, is that it?” she cried angrily.

“Yes: with

your conscious mind. But your unconscious perceptions are very accurate and

very acute, K’t-Ln, you should trust them more. –Yours, too, M’ri,” she said,

smiling at her.

“I know

you’re not bad,” said M’ri shakily.

“I don’t

think I am, no, in terms of what you mean.”

“Who are

you?” demanded K’t-Ln tightly.

Jhl sighed.

“I'm going to tell all of you the lot. As far as I know it. After that we'll

decide whether I ought to erase the knowledge, for your own safety, before The

Mk-L’ster comes back from the city. –Come back to the table, T’m.”

T’m came

slowly. “Are you another Old Woman?” he said in a squeaky voice.

“No!” cried

K’t-Ln scornfully. She paused. “I suppose she might be.”

“She’s an

off-worlder,” objected M’ri timidly.

“Yes. Well,

all your ancestors were off-worlders once. Just sit down. –Ready?”

“Yes,” said

K’t-Ln grimly. The others nodded shakily.

“It isn’t

scary, it’s interesting,” said Jhl mildly.

“Can he hear?” asked K’t-Ln abruptly.

“No.”

K’t-Ln was

about to tell her to get on with it, but Jhl was getting on with it anyway.

After a

considerable period of silence, T’m squeaked: “Are you really a captain?”

“Yes.”

“Ooh, have

you got a uniform?”

“Ghrr-brain,” groaned K’t-Ln.

Jhl smiled a

little. She showed them a picture of her on the bridge in her Durocloth

coveralls. T’m’s face fell. Grinning, she showed them her in Number Ones at a

plasmo-blasted diplo reception on a plasmo-blasted pleasure-planet.

“Two

galaxies!” he gulped.

“Who

was the man?” asked M’ri with interest.

Jhl flushed.

That had sort of crept in. “That was Lord Vt R’aam. In his Fleet Commander’s—

Oh, go on, then.” She showed them Shan in all his sparf-laden glory.

M’ri went

bright red. K’t-Ln gulped. T’m was too stunned even to say “Two galaxies.”

“Space

garbage,” said Jhl briskly. They goggled. “Look, this is the real Shan—as much

as the vacuum-frozen Whtyllian is ever— Never mind.” She showed them Shan going

into battle: the slanted blue eyes blazing, a smile on his lips.

There was a

stunned silence. Finally K’t-Ln croaked: “How many people did he kill that

time?”

“Beings,”

corrected T’m numbly.

“Mm? Oh,

off-hand, a few hundred thousand, I suppose. Well, the better part of a battle

fleet—” Jhl broke off. After a moment she said: “That’s what Space Fleet’s for. The Federation may publicise the

idea of the Rule of Law in the

Encyclopaedia, K’t-Ln, but they’re really far more concerned with being able to

trade what they want, where they want, and with whatever beings they want, at

the prices they decide on, and with being able to grab the mineral rights on

any planet they happen upon that’s unlucky enough to be a goodly distance

outside the Rim and undeveloped enough to be unable to sign a treaty. And

before you ask, any treaties are always on the Federation’s terms.”

After quite

some time T'm squeaked: “Isn’t it supposed to be all of us, though?”

“IG law

represents the collective will of the beings on all the member planets?” said

Jhl, raising an eyebrow.

T’m and

K’t-Ln both nodded.

“That is the

general idea, yes. The voting rights are what you’d see as very fair—well, the

Bluellians approve of them, so in humanoid terms they must be fair. But what

most sentient beings are governed by, as far as I can make out, is greed: not

necessarily greed for possessions in all cases, but that sort of thing. So it’s

fair to say,” she said, aware that quite a few budding illusions were being

shattered here, “that the Federation is ruled by greed. Greed reinforced by

strength, and Space Fleet’s the strong right arm.”

“That’s horrible!” cried M’ri.

“Pretty

horrible, yes.”

“We can

still believe in the Rule of Law,” said K’t-Ln through trembling lips. “And

that—that honour is more important than greed. And oppose beings that try to

put greed first.”

Jhl agreed

kindly: “Yes. We can try.”

“I don’t

want to be a Pilot after all, if the Federation’s like that!” cried T’m

bitterly.

“Well, you

don’t have to be,” replied Jhl mildly.

“Don’t be so

cool and rational about it!” cried K’t-Ln. “Don’t you even care?”

“Not very much, no. Most of my life I’ve

been too busy trying to stay alive to bother about ethical positions.”

“Go on,

sneer!” the girl shouted.

Jhl

scratched her head. “I wasn’t— Oh, Vvlvanian curses! SORRY!” she shouted.

“Look, I can’t take another IG microsecond of this Pleasure Girl mok shit!” She

removed the mini-web and, scratching her head vigorously, swept her hair back

behind her ears with a sigh.

“You look

more like you did in your uniform,” spotted T'm

“You’re not

like her at all,” recognised M’ri faintly.

“Pleasure

Girl Roz? Not much, I sincerely hope,” said Jhl grimly.

There was a

short silence. Jhl was regretting what she’d just said, but after all, it was

the truth. “I wasn’t sneering, K’t-Ln; I respect your attitude, only on a

day-to-day basis most beings put expediency first: that’s what I was trying to

say. Well—life forces you to it.”

“Yes,” said

K’t-Ln, biting her lip. “I see what you mean.”

Jhl didn’t

think she did, entirely: she was too young. And she didn’t think the other two

really understood anything much of what had just been said, except that Space

Fleet were not entirely “Goodies” after all. However, there was a very long

pause. K’t-Ln brooded, T’m scowled, and M’ri looked distressfully from one to

the other of them.

Finally M’ri

said: “Would anyone like a cup of fl’oouu tea?”

“Yes,” said

Jhl thankfully. “And shove a shot of uissh in it, for Federation’s sake.”

“You can

salute and say ‘Yes, Captain,’ M’ri,” noted K’t-Ln drily.

M’ri

blushed. “Should we call you

Captain?” she squeaked.

“No, you’re

not my crew."

“Well, I’m

certainly not,” said K’t-Ln grimly.

By the time

the kettle was boiling T'm had recovered enough to demand eagerly: “Tell me

more about BrTl!”

“Uh—well,

what?” said Jhl foggily.

“How big is

he really?"

“Pretty big.

I could tell you in IG measurements, would that— No. Um—well, it’s mostly neck,

I suppose. If he was here...” She figured out about where BrTl’s hip would

come. The ceiling was too low, she admitted, as T’m asked excitedly where his

head would reach to.

“Galaxious!”

he decided.

“Kna shit,”

noted K’t-Ln.

“Yes:

although his size does come in extremely useful in many situations, it’s not

that that makes him BrTl,” said Jhl.

“I know

that!” he shouted, very red.

M’ri poured

the tea and sat down again. “No wonder you know all those occasions and stuff!”

she said with a giggle.

“EQUATIONS!”

shouted her siblings with furious scorn.

“Oh, yes:

those!” said M’ri with another giggle.

“Yeah. I

shoulda guessed, that time you told me I’d managed to turn my ship inside-out

and park it on top of itself in triple space without even checking the

figures,” said K’t-Ln sourly.

Jhl’s eyes

twinkled but she admitted: “It's a text-blob error, K’t-Ln, anyone with Pilot

training would recognise it.”

“Would

BrTl?” asked T’m keenly.

“Yes,” she

groaned.

After a

little K’t-Ln said: “Do you think the it-being knows everything?”

“I don’t

know, K’t-Ln: it’s as mysterious to me as it is to you. As to why the it-beings

like Trff are apparently content to jog around the universe in the company of

lesser minds like humanoids and xathpyroids, I can’t say.”

“Maybe they

need friends,” suggested M’ri.

“Pooh!”

cried K’t-Ln.

“Well, it’s

as viable a theory as any that any being has ever put forward,” conceded Jhl.

M’ri didn’t

understand “viable” but she understood the general drift, and she smirked.

“Why would

they want to make friends of lesser beings, though?” demanded K’t-Ln.

“I don’t

know. I doubt if the it-being sees anything at all, even the concept of lesser,

as we do, K’t-Ln. I think we’d have to re-think our most basic assumptions in

order to get within a megazillion light-years of understanding a fraction of

the Ju’ukrterian mind.”

K’t-Ln’s

brow wrinkled. “You mean, as fundamental as good and bad?”

“No: far

more fundamental than that. Up and down. Left and right. Light and heavy.

Asleep and awake. Night and day.” She hesitated, then shrugged fractionally and

added: “Binarism.”

“You’re not

joking,” discovered K’t-Ln slowly.

“No.” Jhl

drank tea calmly. “I could go one of those bun-things of yours, M’ri,” she

noted.

M’ri gave a

loud giggle, and bounced up. “Yes, sir, Captain!”

“You will have to erase all this,” noted

K’t-Ln drily.

“Mm.” Their

eyes met: they smiled.

“What? But I

don’t wanna forget BrTl an’ Trff!” wailed T’m.

“No. Well,

one day, if I ever get out of this pile of mok shit,” said Jhl, swallowing a

sigh, “you’ll get to meet them. If we’re not all in a Feddo jail.” She winked

at him.

“On Vvlvania

mining the magma pits!” he choked.

“You got

it,” conceded Jhl. They giggled.

M’ri had

fetched the biscuit barrel. “We might as well finish them. –Who feeds you in

space?” she asked curiously.

“The ship,

of course.”

The

crunching stopped and there was an awed silence.

“You three

don’t need to help me, K’t-Ln,” said Jhl on a cautious note. “I just thought

you ought to know that—well, to a certain degree—our intentions coincide.”

“Ye-es...

What’s the Fleet Commander really want you to do, though?” she demanded.

Jhl shrugged. “I’ve told you as much as I

know. Find Rhan. Send a message.”

“That’s what

I thought,” K’t-Ln admitted.

“You must

love him very much,” decided M’ri softly.

Jhl took

another biscuit, annoyed to find her hand was shaking slightly. “I don’t know,

any more. I thought it had worn off. I thought that was why I was doing it:

because it had worn off and because I owed him one. Something like that. One

last big effort, and then I’d be free of him, I wouldn’t owe him a thing.”

“Did you owe

him anything, though?” asked T’m, faint but pursuing.

“Not

materially, no. But emotionally, I suppose I thought I did: he had offered me

everything a being of his wealth and position could, T’m, and I’d—uh—laughed at

him. When I wasn’t yelling at him.”

“I see,”

said M’ri slowly.

“Well, I

don’t!” said K’t-Ln in a loud and sulky voice.

Jhl gave her

an ironic look. “Mm. Well, I dunno. We go back a long way, me and Shan. He’s

more like an old comrade than anything, I suppose.”

M’ri leant

forward eagerly. “Would you feel worse or better if it was BrTl that had lost

all his mind-functions, though?"

“M’ri!”

cried K’t-Ln in horror.

“I don’t

mind, M’ri, it’s such a relief to be me again,” said Jhl with a smile. “It’s a

reasonable question.” She scratched her head. “It’s very hard to say, because

when you’re a mammal, sex does tend to complicate things, doesn’t it? But I

think it would be as bad. And then, BrTl is my First Officer, I suppose in a

way I’d feel a lot more responsible.” She shrugged a little.

“It’s not as

simple as one or the other, you’re dumb!” said K’t-Ln fiercely to her sister.

M’ri merely

looked smug and drank tea.

After a

moment K’t-Ln said grimly: “Well, do you agree it’s only fair to set the

prisoner free?”

Jhl sighed,

and gave up trying to resolve the dilemma. “Yeah. So—we do it?”

Their eyes

shone, even the timid M’ri’s. “Yeah!” they breathed. “We do it!”

“They’re really going!” gasped T'm, as the

clansmen’s battered old lifter rose slowly from the paddock.

“Yes. The

order’s as real to them as if The Lord had really given it,” said Jhl without

much enthusiasm.

In the warm

kitchen, silence fell. Their momentary euphoria had evaporated. They looked at

one another uncertainly.

“Okay, then:

I’ll do it,” she said.

K’t-Ln had

begun to struggle to her feet. Now she collapsed into her chair again. “You’ll

have to,” she said sourly.

“No! I’ll

come!” cried T’m stoutly.

“Is he tied

up?” quavered M’ri.

“Shackled,”

said Jhl.

M’ri gulped.

“He’s a very

gentle being, he wouldn’t dream of hurting any of us, M’ri.”

“Yes,

but—but he might be very angry,” she quavered. “And—and he is the Regent.”

“Well, you

can curtsey to him!” snarled K’t-Ln.

“I could

bow,” offered T'm.

“Bow if you

like. And come if you like, he won’t hurt you. I’m going up,” said Jhl

impatiently. “Come on, if you're coming, T’m.”

The passage

door closed after them. The Mk-L’ster sisters looked at one another.

“She must

have been in lots and lots of battles,” said M’ri faintly.

K’t-Ln

gnawed on her lip. “Yeah."

“I bet he

will be angry,” said M'ri.

“Shut up!”

she snarled.

Silence

fell.

Upstairs

they looked at the door of the attic room.

“He's not

sending!” hissed T'm.

“He knows

we’re here,” said Jhl mildly. She shot the bolts back and turned the heavy

metal key.

“Go on,”

said the little boy hoarsely.

She put the

blob-key in its lock.

After some

time during which Jhl’s cheeks got redder and redder, T’m squeaked: “Can’t you

do it? I’ll help!"

“That won’t

be any use. The blob will only respond to certain encodings, and he’s got it

set to Jhm M’D’nl’d Mk-L’ster’s and his own— Intergalactic clown!” she shouted,

hitting herself on the forehead.

“Can you

make Jhm M’D’nl’d Mk-L’ster think he’s been ordered to come back?"

“I don’t

think I need to,” she said drily. “Given the available encodings in this neck

of the Old Rthfrdian woods.” She asked the man inside to think Open at the blob-lock.

Just that? he sent in immense surprise.

“DO IT!” shouted

Jhl at the top of her lungs.

The door

swung open before the sound of her voice had died away. Jhl and T’m stared at

the slim man standing shackled in the middle of the small attic room.

Rh’aiiy’hn

of Old Rthfrdia said drily: “I’d have done that months ago if I’d known it was

so—” He gulped. “–Easy,” he finished weakly, staring.

“She’s not

really a Pleasure Girl,” began T’m hastily: “she’s—”

Jhl put a

hand gently on his bony little shoulder. “He knows I’m not,” she murmured.

Rh’aiiy’hn

went on staring.

Finally Jhl

recommended drily: “Close your eyes, it might help to reconcile appearance with

reality. Or to tell one from the other—whatever.”

“Is that

your true appearance?” he said feebly.

She

scratched her head. “Given a few nips, tucks, liftings, lowerings, polishings,

pearlizings—” She felt his hurt bewilderment. “Sorry. Yes. I’m not a

metamorph.”

“She took

the mini-web out of her hair,” the little boy said.

Rh’aiiy’hn

smiled at him. “Did she? That would change her appearance somewhat. You must be

T’m, I think. How’s T’m’s Kitten, today?”

“Good!” he

beamed. “Um—sir,” he croaked.

“‘Great Lord,’”

corrected Jhl drily.

“Great

Lord,” said T’m faintly.

“No: please

just call me Rh’aiiy’hn,” he said.

“So you’re

as much of a federo-demo-nut as is claimed,” said Jhl drily.

“I’m sorry,

Captain, I didn’t understand that,” he said.

“Mm? Oh,”

said Jhl feebly. She’d turned her translator off, it was weeks since she’d

bothered with it. And in any case it was such an up-market translator that it

would probably have switched itself off when her Old Rthfrdian had reached a

respectable level.

“Two galaxies,

don’t you know what that means?” cried T’m, staring at him.

“Being shut

in an attic for six months without benefit of the IG Encyclopaedia is hardly

the best culturing ground for developing a grasp of Intergalactic slang,” noted

Jhl.

Rh’aiiy’hn

passed a hand over his hair. “Has it been that long?”

“So I

gather, yes. Come downstairs, it’s like the vacuum-frozen plains of Gwrrtt up

here.”

“Er—yes. Can

you undo these?” He gestured at the shackles on his ankles.

“Crystallise

them!” urged T'm excitedly.

“Um—hang

on.” Jhl concentrated on the molecular structure of the shackles. Then she

looked at their lock, and smiled. The shackles fell off with a little clatter.

“C’n I have

them?” asked T’m eagerly.

Jhl rolled

her eyes. “Go on.”

He scooped

them up eagerly, not neglecting to cast a wary eye up the man as he did so.

“It’s loads warmer in the kitchen,” he said, going over to the door.

“Yes: off

you go,” agreed Jhl.

T’m

scampered out with his booty.

Rh’aiiy’hn

hesitated; then he said in a low voice: “Thank you, Captain.”

“Are you all

right?” she demanded baldly.

“Yes. I— A

bit weak, it must be the combined effects of confinement and the drug... I had

no idea you were a woman,” he said faintly.

Jhl had

actually grasped that. Although she’d had a good idea of what he looked like,

she hadn’t realised how very like Shan he was: the same golden-tan skin, the

high cheekbones, the winged jaw and the pointed chin, plus the slanted azure

eyes that he shared with his brother. But above the golden skin the hair was a

dark auburn, not Shan’s shining black.

“Possibly

sex is less significant in the scheme of things than we mammalian humanoids are

predisposed by our genetic encoding to believe,” she said grimly. “Come on,

Lord Rhan.”

Rh’aiiy’hn’s

lips twitched a little, but he didn’t correct her pronunciation or the term of

address. He followed her slowly down the first flight of stairs. Halfway down

he murmured: “Is there a scheme of

things?”

The powerful

mind was shielded from him but he saw her slender shoulders shake

infinitesimally, and was very pleased with himself.

Jhl paused

before the last flight of stairs. “I should warn you that M’ri may be overawed

by your consequence and that K’t-Ln, though she wanted to free you, will

probably be very truculent."

“Yes,” he

agreed.

“You’d

better lean on me,” she said abruptly.

They

descended to the ground floor very slowly, the Regent leaning heavily on Jhl.

In the

kitchen she assisted him into the big leather armchair. M’ri was looking in

disappointment at his grubby shirt and shabby riding breeches. Jhl’s lips

twitched but she merely said mildly: “Bring some more wood in, T’m, would you?

Lord Rhan’s rather cold.”

“It’s cold

as the vacuum-frozen plains of Gwrrtt in the attic!” T’m informed the company,

as he scrambled for the back door.

Jhl

introduced the Mk-L’ster sisters and he said, smiling at them: “Thank you for

helping to set me free.” Disconcertingly, it was Shan’s smile, but this was a

far gentler and much, much nicer personality.

K’t-Ln

growled that they hadn’t done anything and he pointed out, very nicely, that

they had agreed that that something should be done, which was what counted.

Whereupon M’ri suggested a cup of tea, blushing and dropping a shaky curtsey.

“It had

better be khyai’llh tea,” said Jhl briskly before the Regent could speak. She

dropped a hand on his shoulder. “He’s shivering: it’s reaction. Not to say

withdrawal from that muck they’ve been feeding him. Get him a warm rug, M’ri,

and then the tea.”

M’ri didn’t

giggle and say: “Yes, sir, Captain!”, she just nodded silently and scurried

over to the big carved wooden chest that held a selection of rugs and some

battered leather pouches. Jhl assumed she was in awe of the Regent, grubby

hunting attire notwithstanding, not realising that she had spoken to the girl

as she might have to a very junior member of her ship’s crew, and it was not at

this moment the Regent of whom M’ri was in awe.

Rh’aiiy’hn

of Old Rthfrdia, who was also accustomed to command, had realised it, however.

He leant his head back and closed his eyes, trying in vain to reconcile the

dainty, black-haired physical presence of the girl who had rescued him with the

personality that took for granted that its orders would be obeyed and the powerful

mind that controlled it.

It was late

afternoon when he woke from a doze to find himself alone in the kitchen but for

a stripey cat on the shabby hearth-rug. The fire was almost out. He was looking

round him dazedly, trying to gather his wits, when the back door opened and a

slim figure in baggy nyr-hide breeches came in, lit by the glow of afternoon

sunlight.

“Hullo,

Captain,” he said weakly.

Jhl grinned.

“I thought I might as well get out of that vacuum-frozen draped garment I was

masquerading in.”

He smiled a

little. “Was it the Lady A’ailh’sa’s?”

“Yeah: last

year’s!”

His lips

twitched. “The ladies of the Court are all like that.”

“So I

gather. Fancy a shot of uissh?”

“Er—yes. If

you think I should?”

“If you pass

out, we’ll know you shouldn’t have,” she replied equably, pouring.

He gave a

little shrug, and drank.

“You haven’t

passed out,” she noted.

“No.” He

looked at the open back door, and sighed. “It’s wonderful to see freedom and

know I could just— Could I just walk

out into it?” he asked with a wry smile.

He wasn’t

reading anything from her, that was

for sure. Well, he wasn’t stupid. Jhl made a face. “Only as far as the lifter

paddock. We haven’t decided what to do with you yet. And I can’t decide how

much you should know. Do you know who your father was?”

“A Whtyllian

lord. –You must be able to read it all,” he murmured.

“Yes. I’m

checking up on you. It’s less tiring, too."

“I see,” he

said slowly, frowning. “I’m sure you would win, if it came to a tussle of minds

with my brother.”

She eyed him

drily. “Uh-huh.”

“What is

it?"

“I’m

wondering what would happen if the pair of you ganged up against me.” She added

with a grin, re-filling his glass: “Shan always said I’d make a rotten

commander: no grasp of strategy.”

“No,” he

said, smiling slowly. “–Who is Shan, an old comrade?”

Jhl could

see he really didn’t know and had made no connection between the name and the

mention of his father. As Shank’yar had once mentioned, Rh’aiiy’hn’s mother had

never been privileged to learn his father’s real name. She was tempted simply

to open her mind to this son of Shan’s, who was at once so like and so very

unlike his father, but that would have been poor strategy indeed. So instead she

told him as much as she’d told the youngsters.

Rh’aiiy’hn

rubbed his pointed chin slowly. “I see. Has he a hidden agenda, do you think?”

Jhl hadn’t

suggested this: she was pleased to see he’d thought of it for himself. She

nodded silently.

“Mm. Not

merely Drouwh’s pwld mines?"

“I really

don’t think so. The Vt R’aams are already immensely wealthy. So while he

wouldn’t say no to becoming the richest being in the Known Universe, that

wouldn’t be an end in itself. –Too boring,” she explained with a twinkle.

He nodded,

and after a moment asked: “Does he have other sons?"

“Not full

sons, no: you and Drouwh are the only ones that he endowed with a full share of

his genetic encoding.” He didn’t understand, not surprising in a being from a primmo

little world like Old Rthfrdia. She explained calmly. Rh’aiiy’hn evinced

neither surprise nor distaste, which did surprise Jhl considerably.

“I think he

may be looking for an heir, then,” he said slowly.

“Yeah. Why

in Federation couldn’t he have waited until after F-Day?” she demanded on a

cross note.

“Is that

what off-worlders call it?” he said, his lips twitching. “I think possibly he

thought I might not be alive by F-Day. Perhaps he wanted you not only to find

me but to see that I’m kept safe. Indeed, to rescue me, as you have done,” he

said politely.

Her eyes

twinkled. “You’re unlike him in many ways, but you’ve got that in common, at

least! Um, it’s hard to explain: that way of... ironically distancing yourself

from yourself and your own situation, I suppose. –Drouwh doesn’t do it at all,”

she added, half to herself.

Rh’aiiy’hn

looked at the little frown on her ivory forehead and said softly: “No?” And

wondered if she knew that he was reflecting that possibly that was a point in

his favour, then, and if she could sense the galloping of his heart; and knew

bitterly that the answer to both these questions was undoubtedly Yes.

Jhl

swallowed. After a moment she said: “Don’t feel like that.”

“Like what?”

he returned on a harsh note.

“Humiliated,” she said, licking her lips. “I have to do it, at this

stage: I have to be sure of you. And even if you’d done the Course, I doubt if

you could shield your mind from me: I’ve got too strong. But once I’m sure I

can trust you, I won’t look. –Unless I have to,” she added honestly.

He smiled a

little but said curiously: “How can you not look?”

She eyed him

drily. “Well, apart from the fact that in most parts of the Known Universe it's

considered cursed bad manners to look without permission, the Course teaches

you how not to.”

A dark tide

of red rose up the strong neck that was so like Shan’s and he said: “I suppose

I’ve been prying into other beings’ minds all my life. Unthinkingly assuming

that because I had the ability, I had the right.”

“Everybody’s

like that at first.”

“Hardly for

forty years, though,” he said on a bitter note. “Do you despise me?”

“No. I just

said: everybody does it; until the Course or maybe their own society teaches

them different.”

“Which was

it for you?” he asked, looking into the big dark eyes.

Jhl grinned

cheerfully. “Oh, the Course! I’m a Bluellian; not many of my people have mind

abilities, either. Uh—sorry: the Intergalactic Mind-Control Course.”

“I see. –I

do know of Bluellia: grain and grqwaries, mainly. Plus some tourism?"

Jhl nodded

feebly. Even though his mathematical ability was almost zero, his mind held a

childlike image of the two galaxies, and he had situated Bluellia pretty

accurately in it. “You know more than most Old Rthfrdians, then.”

“Yes. As a

member of the Royal Family I was given a solid grounding in intergalactic

economics and history, trade, diplomatic matters—that sort of thing.”

“I see.” She

had seen a picture of two lonely little auburn-haired boys in a large schoolroom,

grinding away over their lessons whilst outside the rest of Old Rthfrdia leapt

and played in some sort of summer festival.

Rh’aiiy’hn

laughed weakly. “Feeling sorry for myself, I’m afraid! At least there were the

two of us, it would have been much worse alone.”

“Uh-huh. Not

your brother: your cousin, is that right?”

“Yes. Jhms

All’yhaiyn. I miss him,” the man said.

“Yes,” said

Jhl gently. “So the boy Ruler is your cousin’s son, is that right?”

“Yes. He

calls me ‘uncle,’ but that is the relationship.”

There was a

short silence.

Then Jhl

leant forward. “Lord Rh’aiiy’hn, why don’t you want to abolish the monarchy?”

Rh’aiiy’hn

sighed. “Surely you— Oh, very well. I swore to Jhms All’yhaiyn on his deathbed

that I’d do my best for the boy until he reached the age of majority. To my

mind that doesn’t entail throwing his inheritance away, whatever my own

position on monarchy, constitutional or absolute, might be.”

She could see clearly enough that his own

position could well be summed up as outright socialism: Choice 8,096—something

like that? It was written up in the Bluellian Archives somewhere, no doubt, but

they’d been in the Federation for so many generations— “So your word is your

bond?” she said flippantly.

His lips

tightened. “Can we not argue about it, please, Captain?"

“I’m not

arguing: I can see there are circumstances where you would break a promise to a

dying being.”

Rh’aiiy’hn

leant his head against the back of the big leather chair and sighed. “Yes. I

suppose there are.”

Jhl looked

at the strong golden throat in the open-necked, coarsely-woven shirt and felt

absurdly shaken.

There was a

long silence in the old kitchen.

“Possibly,”

the man said at last with a sigh, “Drouwh and I might have been able to reach

some sort of agreement over the question of the monarchy—at least an agreement

that the question could be left until the boy comes of age—if it wasn’t for the

business of the clan lands. -Am I making sense?” he asked suddenly.

She nodded

and he passed a hand over his face and said: “Of course. Even if he hasn’t

spoken to you of his position, you must have read— Yes."

“I needn’t

necessarily have been interested, however,” noted Jhl, very dry. The more so

because of that shaken moment, earlier.

“Er—no,” he

said, looking at her with a startled expression and a certain mental recoil.

“Go on,” she

said, swallowing a sigh.

“We haven’t

been able to reach an accommodation. He insists on the minimum devolution of

clan lands dictated by IG law: fifty percent by area to the people.”

Jhl just

waited.

“I can see why!” he said on an irritable note. “You

must be able to see— I’m sorry. No, well, in the short term of course it would

create far less furore than full devolution. It might even keep the Lords quiet

for the next generation. And of course it’s less likely to stir the townsfolk

up against the clanspeople. But... I can’t reconcile it with my conscience.

–Possibly you’re more aware of my motives than I am, and you can see it isn’t

my conscience at all,” he added with a tiny, twisted smile. “But to put it

simply— No, that’s wrong,” he said, frowning. “To put it as truthfully as I can, nothing short of

full devolution seems fair to me. Drouwh’s way leaves the Lords still with

immense wealth and the people with nothing very much. The fifty percent by area

that their Lords choose to allot them, in fact."

“I agree

with you: it isn’t fair.”

He looked at

her doubtfully.

“On the

other hand, I agree with him that the fifty percent solution seems the least

likely to lead to outright blood-letting. It’s a far more practical approach. –I

agree with both of you, in short,” she added, very dry indeed.

Rh’aiiy’hn

sighed. “Yes.” He hesitated. “And on the monarchy?”

She made a

face. “Now that I’ve heard your reasons, I agree with both of you there, too.”

“Bears’

claws,” said Rh’aiiy’hn, very faintly.

Jhl got up

abruptly and strode over to the open door. She stood glaring out across the

vehicle paddock with her back to him.

Rh’aiiy’hn

watched her for a while. She didn’t turn round. Finally he said: "Where

are the children?"

“Mm? Oh:

T'm’s gone into the forest in search of some sort of edible fungus—not lr,

something else—and K’t-Ln and M’ri are just outside on the grass.”

He rose and

came slowly up to her shoulder. K’t-Ln was sitting up very straight with her

bow in her hand while M'ri was placidly sewing. “Aren’t they pretty?” he said

with a smile in his voice.

“What?

Uh—yes, I suppose so.”

There was a

short silence. “When is Drouwh due back?” he said hoarsely.

Jhl sighed.

“Another three days.”

“And if he

should be early?”

“I’ll hear

him.”

“I see.” He

swallowed. “I’m very fond of him, you know,” he said in a low voice.

“Yes,” said

Jhl vaguely. “Uh—yes,” she said, blinking suddenly. “How long have you known he

was your half-brother?”

“For a very

long time. Mother has always known: my father told her. According to him it was

in the nature of a genetic experiment. I don’t know if that was true or not.

But certainly by the time he turned to the lady poet of the Lower Cwmb—I’m

sorry, that’s Lady Mk-L’ster—Mother had refused several times to leave Old

Rthfrdia and become his wife. Forgive me, I’ve forgotten the IG term.”

“IG-legal

bond-partner. Yes, apparently his mother has always been keen to see him bond-partnered

to a—” Jhl paused. “Princess,” she said in Old Rthfrdian, very dry.

“Yes. But a

member of the Old Rthfrdian Royal Family does not desert her duty.”

She was

gazing vacantly across the grass and he realised she wasn’t really interested

in the topic. Certainly not in him, Rh’aiiy’hn, as an individual being. At the

most as a—a genetic experiment! he thought bitterly.

Eventually

she said: “Drouwh has no idea you’re brothers. I can’t understand why he never

picked it up from your mother.”

“I doubt if

he ever bothered to look. The point never occurred to him, you see. Do you

think it will be a great shock to him, when he does find out?”

Jhl replied

simply: “You know him better than I do, what do you think?"

A flush rose

to the high cheekbones; he said angrily: “How can I possibly know him better

than you do?"

“I know the

structure of his mind and his biochemistry and his genetic encoding. I know him

on a cognitive level, I suppose. Of course I can recognise and classify his

emotions, but that isn’t the same thing as having known him all his life as...

as an individual being,” she ended on a dubious note. “That doesn’t put it very

well; I’m not used to talking about this sort of thing.”

“You mean my

knowledge of him is more... instinctive? Intuitive?”

Jhl

shrugged. “Non-cognitive, anyway. –So?”

Rh’aiiy’hn

bit his lip. “I think it will be a great shock to him. The more so since he

doesn’t even know his father was an off-worlder.”

She shook

her head. “He’s pretty sure of it, now. The Old Woman said to him, quite

casually, that the man he thinks of as ‘the Dad’ wasn’t his father. That

doesn’t worry him, but he doesn’t like the idea that his powers may be from an

off-worlder.”

He winced.

“He wouldn’t, no. Our Old Rthfrdian traditions are very dear to him, but it’s

more than that… How can I put it? I think it’s a matter of his conception of

his self-hood. Most Old Rthfrdian clansfolk feel themselves to be deeply linked

to the land in a way I can’t explain.”

“Ye-es...

Isn’t it the female line that matters, with the clans, though?"

Rh’aiiy’hn

smiled suddenly. “You’re rationalising it, Captain! I see what you mean by

understanding him on a cognitive level. Legally, socially and—er—genetically, I

suppose, it is traditionally the female line that is considered to matter, but what

I’m talking about is a matter of feeling, not of law or social custom or

genetics.”

Jhl nodded.

“I've never been any good at emotional stuff,” she said casually.

He

swallowed. “Er—I see.”

“Having

mind-powers doesn’t turn you into a different personality,” she said drily.

“No-o... But

you have always known of your powers, surely, Captain?"

“Not

entirely.” She shrugged. “Oh, well—” Rh’aiiy’hn listened with interest, not

speaking. “I’m still me, essentially,” she finished.

“Ye-es... I

see. Yes,” he said, very softly: “one has power over others, not over one’s

self... over the physical shell, yes, but not...” His eyes turned inward, and

became remote. Jhl could feel he was taking a second look at his own

capabilities. She didn’t pry. Finally he said: “Could you alter another

person’s—I beg your pardon—another being’s personality, Captain?”

“No. I could

make the being believe different things about itself, but I couldn't alter its

fundamental self.”

“Mm...”

“One would

be as immoral as the other,” she noted drily.

“Yes.

–Captain,” he said slowly: “am I right in thinking that the principal reason

Drouwh kidnapped me was that his faction found it impossible to make any

headway with me reading their intentions?”

“Yes. He can

see as clearly as you that it’s now given his side precisely the sort of unfair

advantage that you had before, if that’s what you were going to say.”

“No,” he

said, shaken again to find she wasn't reading what he was going to say before

he’d said it. “No... Listen, Captain,” he said with considerable forcefulness,

“I fully appreciate your dilemma. Simply to take me back to the Court would

merely replace the current unfair situation with the former one. So what I’m

proposing is that you temporarily remove, or block, both my mind-powers and

his. Until the Referendum’s over.”

Jhl gulped.

“Can

you?"

“I think

so... I never thought of that,” she said feebly.

Rh’aiiy’hn

smiled pleasedly.

“You look so

like him when you smirk like that!” she said in a shaken voice.

“Like

Drouwh?”

“No. Like

your father.”

“Oh. I

didn’t think I was smirking, precisely."

Jhl smiled

crookedly. “No, you weren’t. It was just the—the expression. You’ve got his

intelligence and his good looks, but you’re not very like him, really.”

“If he’s the

devious character you've described, I'm rather glad of that!”

“Mm,” she

agreed on a wry note.

“Well, what

do you think?” he said hopefully. “Could you do it without hurting Drouwh?”

“Um... He’d

have to let me, or be asleep, I think. Um, yes, I could make him believe he’s

never had any powers. People would notice, though.”

Rh’aiiy’hn

rubbed his jaw. “That’s a point. I suppose they’d notice with me, too."

“Well, yes, if your faction’s in the habit of

asking you what Representative So-and-So's thinking!” she said strongly.

He smiled a

little wistfully. “Something like that. I haven't really got a faction.”

“You could

have fooled me!”

“No. There’s

only a handful of us. Off and on we’ve had a precarious alliance with the

conservative group led by old Lord Fh’Ly’haiyn and Rh’n’lhd, but the only thing

we have in common with them is a desire to preserve the monarchy.”

Jhl looked

at him incredulously. She looked into his mind. “Bones of Brqa,” she said

numbly. “And most of them wouldn’t half mind getting rid of you!”

“Exactly.

They’ve got hold of Allie, without me to protect him, I’m afraid. No doubt

filling his head with their reactionary rubbish,” he said tightly. “I beg your

pardon, Captain: All’yhaiyn, the Ruler.

Jhl smiled

suddenly. “Is that his name? Drouwh thinks of him as ‘the boy.’”

“He’s not so

unlike Fh’Ly’haiyn and Rh’n’lhd as he fancies, then,” he noted drily.

Choking

slightly, Jhl said: “Yeah! Um... Well, if it’s that bad, and I send you back

without your mind-powers, you won’t be safe.”

He shrugged.

“I can take my chances.”

“No, Shan

didn’t send me all this way for you to end up with a dagger in your back. –I’m almost sure,” she muttered, grimacing.

She scratched her head. “I suppose I could go back with you: watch your back.”

“Wouldn’t I

wonder who you were, though, Captain?” he said politely.

Jhl laughed

suddenly. “Sometimes you do sound just like Shan! Look, do you think you could

stand it if I left your memory of your powers, and only blocked the powers

themselves?”

Rh’aiiy’hn

went very pale. “I think so.”

Jhl frowned

over it. “I think it’s the only fair way. The same with Drouwh, I think...

Though I think I’d better erase his memory of me.”

“Erase?”

“It’s easier

than blocking a memory. But I’ve been practising with Stripey. I’ve got quite

good at blocking specific memories, now. I suppose it would be morally

indefensible to erase a memory of Drouwh’s just because I’ve got an uneasy

feeling it might be safer for me if I did."

“It most

certainly would!” he said strongly, missing the dry note, unaware that his

response was precisely what she had expected from him.

“Yeah.” Jhl

leant against the door-jamb, gazing out across the wide stretch of lawn to the

old stone wall and the forest.

“Could we go

outside for a walk before you do it?” he said in a low voice.

“What?” she

said, jumping. “I'm not going to do it right this minute, you intergalactic

clown!"

Rh’aiiy’hn

of Old Rthfrdia stared at her, his winged jaw sagging.

“Oh—Vvlvanian curses,” said Jhl limply. “I'm sorry. I suppose that was

what you call lèse majesté, here.”

“And for

which we’d throw you to the bears—mm,” he murmured. “No, it was... salutary!”

Although he

was smiling, Jhl could see he was remembering his dead cousin and reflecting

with some bitterness that since Jhms All’yhaiyn’s death there was no-one in his

life who used that unceremonious tone with him. She looked hurriedly away from

the memory and said gruffly: “Of course we can go for a walk if you feel up to

it, Lord Rhan.”

“Yes. –Just

‘Rh’aiiy’hn’,” he murmured.

“Yes. Sorry.

Rh’aiiy’hn.”

They walked

slowly out onto the grass.

“May I ask

what your name is? Or would it be safer for you if I know you only as ‘Captain’

and—what is it the children call you? Roz?”

“It might be

safer for Shan,” admitted Jhl. She gave him a quick mind-picture of Shank’yar

playing with his toes, and L’Thea masquerading as her in the Mullgon’ya nursing

home.

“Bears’

claws,” he said, shuddering.

“Don’t let

any of the kids see that, will you?”

“No,” he

said faintly.

“I can’t see

how you knowing my real name would endanger Shan, but he’s got a lot of

enemies. I think it had better be Need-To-Know only."

“Er—what? Do

you mean I don’t need to know it?”

“Yes.” Jhl

looked dubiously at her translator. It was off: she repeated slowly in Old

Rthfrdian: “Need-To-Know only. It’s a Space Service term.”

“I see.”

Rh’aiiy’hn clenched his fists and added in a low voice: “And if I said I did

need to know?”

Jhl replied

in a hard voice, not looking to see why he thought he did: “I’d say you

didn’t.”

Rh’aiiy’hn

said nothing. He walked on slowly towards the old stone wall at the back of the

vehicle paddock, long mouth tight.

Jhl could

both see and feel he was overtiring himself. But as he didn’t ask for help, she

didn’t offer any. Finally he reached the wall and dropped onto it with a sigh.

She came up slowly. “Lovely day,” she said.

“Indeed.”

After a moment he added with some difficulty: “Is your part of Bluellia like

this, Captain?"

“Much

flatter.” She looked around her and said: “The colours are basically the same,

though. Blue sky, green grass. Standard c-based, o-breather territory, really.”

“What?” he

said dazedly.

Jhl

glared at the translator, which was still off, and said loudly to it: “He

didn't understand that, hunk of space junk!”

The

translator immediately replied: You

phrased it correctly. His knowledge of Basic Bio is at fault, not your Old

Rthfrdian.

“YES!” she

shouted furiously, hauling it off and hurling it down the lawn. “And SHUT UP!”

“Was it

communicating with you?” asked Rh’aiiy’hn numbly.

“What? Oh.

Yeah, it’s the latest model. Fleet Commanders and up: Shan got it for me.” She

sat down beside him, sighing. “It’s never actually had the plasmo-blasted cheek

to speak to me directly, before, though.”

His lips

twitched.

“What?” she

said suspiciously.

“Well, I

know very little about blob technology, Captain,” he said apologetically, “but

if it’s as sophisticated as you say, possibly it’s—er—learning from you at the

same time as—?” He paused delicately, eyebrows raised.

Jhl laughed so much she nearly fell off the

wall. “You’re more—like Shank’yar—than I thought!” she wheezed.

Rh’aiiy’hn

smiled. But to himself he thought on a bitter note, trying not to care if she

was listening: Not enough, though, am I?

Jhl wasn’t

listening. She was very tired. She sat on the old stone wall in the sun,

quietly soaking up warmth, senses just enough on the alert to be aware of any

approaching being, not thinking at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment